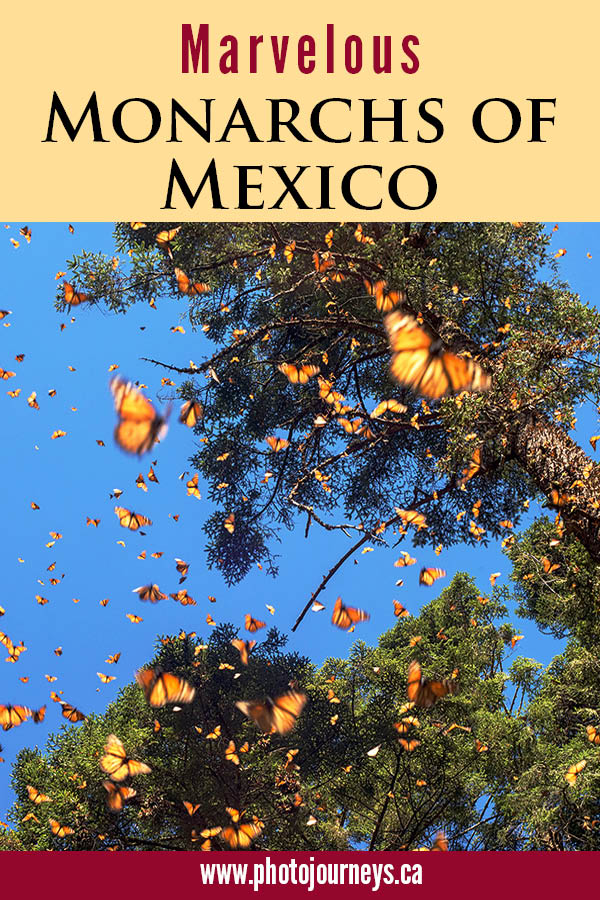

As soon as the morning sun warms the air, the forest and sky spring to life. Bold splashes of orange speckle the blue sky as countless monarchs take flight and land on branches, logs, the ground, and even on our heads and shoulders. The sound is unlike anything we have heard before: a gentle, whispering whir like a million pieces of confetti swirling in the air. Awestruck visitors speak in hushed tones, moving slowly and carefully so as not to disturb or step on the countless butterflies.

It’s simply one of nature’s most breathtaking spectacles. High in the Sierra Madre Mountains west of Mexico City is the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site where migrating monarchs from east of the Rockies throughout North America over-winter in a mountaintop forest of oyamel fir trees. Arriving around late November and staying until March, they number in the millions.

No other butterfly in the world migrates this far and in such large numbers. Their travels are more like bird migrations, but with a twist. Those arriving next year might be the grandkids or great-grandkids of this year’s migrants. How they find their way is still a mystery. It wasn’t until the late 1970s that researchers finally solved the riddle of where the Monarchs spend the winter. Of course, the locals knew they were there. But if you’ve always lived with butterflies, why would you think that it was anything unusual?

Easy to Visit

The best news is that it is easy and remarkably inexpensive to see this wonder of nature. While organized tours from Mexico City, Morelia, and other places abound, visiting independently is fairly straightforward, although it helps if you know a bit of Spanish. On your own, you have the flexibility to stay longer in case the weather doesn’t cooperate. Even a slight change in the weather can have a big impact on what you see.

Four main areas of the reserve are open to visitors. The largest and easiest to visit is El Rosario, up the mountain from the small valley town of Angangueo, about four hours by bus from Mexico City. Visitors can only wander around the site when accompanied by a guide; guides are provided with the modest admission fee. We lucked out in being assigned Filiberto who had worked at the reserve for many years and was a fountain of knowledge.

From the reserve entrance, it’s still a bit of a walk uphill to where the butterflies hang out. We could feel the altitude of over 3,000 metres, and had to take it easy. When we saw the first clump of trees thick with butterflies, it wasn’t immediately apparent what we were looking at. It was as if the branches were twice their normal thickness, but a closer look revealed layer upon layer of butterflies clinging to the branches. In places the masses were so thick that they completely obscured the green needles of the tree. It isn’t unusual for branches to break under their weight. Monarchs’ brilliant orange wings appear a more muted brownish-orange when they fold them to rest.

Weather concerns

Early mornings can be quite cool, sometimes just a few degrees above freezing. If the weather stays cool, or even if it gets cloudy, the butterflies will stay on the trees. But as the sun gradually warms the air, the monarchs become more active.

The best part was that we arrived in ideal conditions, sunny and warmer than usual for mid-February we were told. By late morning the monarchs took to the air by the thousands upon thousands. The scene was nothing short of magical, and it kept getting better the farther we went. At one point, we looked over an area of the forest where almost every tree branch was drooping with heavy layers of butterflies, in addition to those in the air that almost blocked the sky.

As a general rule, visitors are supposed to limit their time at the main viewing areas to reduce congestion. But since there weren’t many people around on our Tuesday visit, Filiberto gave us all the time we wanted.

If there is one main thing to take away from this article, it’s the importance of visiting on a weekday. Visitor traffic is light during the week, even though this is prime monarch season. Things change dramatically on weekends when day-trippers from Mexico City descend on Angangueo.

While we were fortunate to have great weather, it’s not something we can count on. Filiberto tells us that had we come at this time a year ago, we would have been ankle deep in snow. The occasional snowstorm or frost can be disastrous, killing millions of butterflies.

On a Wing and a Prayer

After a couple of hours, we leave with a feeling of exhilaration, tempered with the realization that this marvel of nature is threatened. Monarchs are pressured from a number of fronts. Key parts of the forest are set aside as wildlife reserves, but there are ongoing threats from logging interests, and authorities are constantly on the lookout for illegal logging.

Altering habitats in Canada and the United States is a serious concern, especially the loss of milkweed, which monarch caterpillars feed on exclusively. One culprit that scientists point to is the increasing use of genetically modified crops, especially corn and soybeans along migration routes. These crops have been developed to be resistant to glyphosate, so when the herbicide is sprayed, everything but the crop is killed, including milkweed. Glyphosate, better known by its trade name Roundup, is one of few herbicides that will kill milkweed.

The biggest wild card is climate change, which in the long run may prove to be the most disruptive. Not only is milkweed harder to find, but its quality decreases with higher temperatures. Monarchs time their reproduction and migration according to environmental cues, the most important being temperature. One change anywhere along their complex migratory system could upset the whole applecart.

Yet, as we stand on this Mexican mountain top beneath the orange-speckled blue sky, it’s hard to be pessimistic. Indeed, some of the most positive developments are happening right here. Monarchs have been a boon to the local economy in these remote highlands, long dependent on mining and subsistence farming.

While tourism is important, it is very much a grass-roots endeavour. Locals run everything from guiding in the reserve to providing transport, serving meals at food stalls, and renting horses to make the climb up the hillside. They have become strong voices for conservation, with everyone we met being fiercely proud of their “mariposas”.

The Photography Experience

To capture the phenomenon of a gazillion butterflies in the air, it’s essential to go when it’s warm. During our visit, prime time was around midday. Midday light generally isn’t ideal for photography, so it’s a trade-off. If you go too early and it’s cool, the monarchs might stay on the trees.

A wide-angle lens is great to capture the grand scene, although a telephoto is also useful to zero-in on individuals and clusters. While a fast shutter speed helps to stop the action and better your chances of getting sharp images, don’t overlook purposely using a slow shutter speed to blur some of the butterflies in the air, heightening the feeling of movement.

We found that manual focus worked best. Focus on a tree branch in the middle of the scene, for example, and leave it there. With so much movement in the air, the autofocus is constantly searching, resulting in more fuzzy images.

Feel free to PIN this article

Fantastic ! I’d be interested in combining a trip to Mexico City to Our Lady of Guadeloupe sites and to monarch’s.

That sounds great. Hope you are able to do the trip.