All photos © Robin and Arlene Karpan

Coffee is one of life’s simple but most enjoyable pleasures. We have drunk a lot of it in our travels—some great, some okay, and some best forgotten. We often hear about places having a coffee culture, but what does that mean? Is it enough to have a lot of coffee shops or does it run deeper than that?

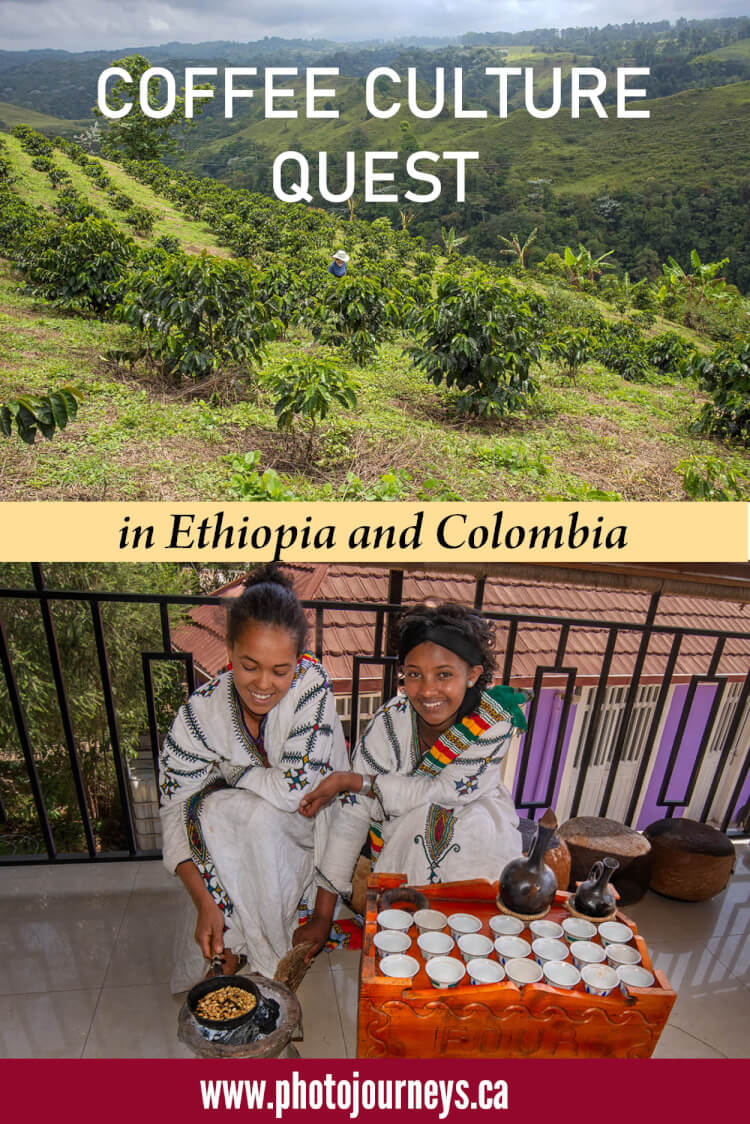

In our experience, two quite different countries on opposite sides of the globe stand out. In both Ethiopia and Colombia, coffee is not only rooted into the culture but is ingrained into the national DNA. These are the places where we have enjoyed coffee the most, primarily because a great-tasting brew is only part of the experience.

Ethiopia – Where it all Began

Coffee pervades every aspect of Ethiopia’s identity – historically, culturally, socially, and economically. They even have a saying that “coffee is our bread”. Some 15 million Ethiopians work in the coffee industry, many being growers on small landholdings. Half the coffee produced is consumed domestically, and coffee is the country’s most valuable export by a long shot.

Everywhere we went, from big-city restaurants to tiny hole-in-the-wall coffee shops in the countryside, the coffee was consistently great. Perhaps we shouldn’t have been surprised since Ethiopians have been drinking the stuff longer than anyone on the planet.

Thank a Goat for Your Morning Eye-opener

The legend of coffee’s discovery has several versions but it usually involves a goat herder named Kaldi in the Ethiopian highlands. The herder noticed that when the goats ate the berries from a particular type of tree they became a lot more spirited and started jumping around. Curious, Kaldi tried a few berries himself and was amazed by how alert he felt. “This must be a miracle,” he thought, so he took some of the berries to show to the abbot at a nearby monastery.

Rather than being impressed, the holy man cast the berries into the fire in disgust, assuming that this must be the work of the Devil. But after catching a whiff of the heavenly aroma coming from the fire, he had a change of heart. The monks retrieved the partially burned berries from the fire, dissolved them in hot water, and the world’s first cup of coffee was born. If it didn’t happen exactly this way, it certainly should have.

Coffee Time Ethiopian Style

Coffee in Ethiopia is not something to simply gulp down for a caffeine fix. No one walks around with go-cups. Coffee is for sipping slowly and savouring and, above all, a time for socializing. The enjoyment can even start before the coffee is poured. In the northern city of Gonder, we had lunch at a well-known restaurant, The Four Sisters, simply named for being owned and operated by four sisters. They prepared the coffee from scratch, starting with green beans roasted in a pan over a charcoal fire. After completing the roasting, servers took the pan around the room to each table so that diners could appreciate the aroma.

We were in Gonder to start a five-day hiking and camping trip through the nearby Simien Mountains, a wild land of breathtaking jagged peaks, rare plants and animals, and small remote villages that seem straight out of Biblical times. We were close to 4,000 metres for much of the trek, where the thin mountain air often drops below freezing overnight. To no surprise, our cook Estefen took the same care brewing fresh delicious coffee in the middle of the wilderness as would any coffee shop in town. Coffee never tasted so welcoming as on those frosty mornings in camp. Yet the best was still to come.

A constant companion throughout our hike was Jamale, who works as a Scout for Simien National Park. Never without his trusty Kalashnikov rifle, his job is to protect hikers. Jamale, along with his wife and two kids, lives in the tiny village of Chenek where we ended our trek.

The Coffee Ceremony

Before the van arrived to take us back to Gonder the next day, Jamale invited us to his house for a traditional coffee ceremony to celebrate the end of the trip. This centuries-old, ritual-rich tradition is practised widely throughout the country, with some regional variations. While coffee is always savoured and not rushed in Ethiopia, the coffee ceremony takes things to another level. It’s partially about coffee but even more about hospitality, socializing, and honouring guests. It’s not for those in a hurry or concerned about caffeine overload.

Jamale’s house is modest, simply built of corrugated metal with a hard-packed dirt floor and sparse furnishings. But when it comes to serving coffee, there is nothing simple about it. Jamale’s wife is in charge of the ceremony. First she washed green coffee beans in warm water. She then put them in a pan to roast over a charcoal fire. The green-earthy smell of the raw beans transformed magically into enticing rich floral aromas that wafted through the house. When done, she ground the beans using a mortar and pestle, then added the coffee to a pot of hot water.

When the coffee was ready, she poured it into small handleless cups. Pouring is an art in itself, with graceful movements and a bit of a show as she holds the pot about a foot above the cups and pours in a long stream, filling the cups to the brim without flowing over. This is the first of the three cups required by protocol during the ceremony and the most potent. It tasted like an extra strong espresso.

She then added water to the coffee twice more and brewed it again in the same grounds for our second and third cups. While not as strong, the next two cups were still rich and flavourful. Each of the three cups in the ceremony has names – Abol, Tona, and finally Baraka which means “to be blessed”. According to legend, these were the names of Kaldi’s goats in the original discovery of coffee story.

Though steeped in time-honoured observances, our visit of just over an hour was casual and relaxed, putting us at ease. Neighbours wandered in for coffee and conversation while kids scurried about. We did indeed feel blessed to be included.

After all that caffeine, we also felt a bit like Kaldi’s goats.

Colombia’s Cultural Landscape

Here too, coffee is synonymous with the country’s identity. UNESCO even placed the Coffee Cultural Landscape of Colombia on the World Heritage List. It recognizes the coffee region as an exceptional example of a unique cultural landscape that is both productive and sustainable. Small farming plots exist in harmony with the high mountain forest, and strong local traditions passed on through generations continue to thrive.

Our coffee quest brought us to the small town of Filandia along the western slope of the Andes in the heart of Colombia’s coffee country. What immediately caught our eye was the riot of colour on Filandia’s buildings. Residents aren’t shy about embellishing a wall or even a single doorway with a hodgepodge of intense reds, pinks, greens, purples, or practically any other shade you can think of.

Life revolves around the centre square, dominated by an imposing church and scattered with park benches where folks come to relax or visit. Then there are the coffee shops. Lots of them. Each side of the square is lined with restaurants or combination bakeries and coffee shops, most with tables spread along the sidewalk. Even the side streets bustle with more of the same. They are always busy since Colombians drink coffee throughout the day and well into the night.

Second only to coffee itself, the other iconic symbol of this region is the old Jeep. Not the newfangled models that look like any other SUV, but classic originals from the 1940s and 1950s. Years ago they replaced mules as the workhorses of coffee country. They can haul heavy loads, such as several bags of coffee, and are suited to the rugged mountainous terrain. Many are lovingly restored and painted in the dazzling colours that Colombians prefer.

Visiting a Coffee Farm

To see how coffee is grown, we arranged a visit to a nearby farm. Coffee farmer Nicolas Spath picked us up in his 1954 Willys Jeep. We likely would have been disappointed with any other type of vehicle. Slowly we bounced along a narrow gravel road while gazing over emerald green hills and valleys dotted with small landholdings.

Our biggest surprise was the size of coffee farms. Colombian coffee is world-famous, after all. Surely, huge plantations must be cranking out the stuff to meet demand. Instead, the vast majority of the more than 500,000 coffee growers are family farms averaging less than five hectares.

Colombia’s terrain is not suited for large-scale mechanized production. Coffee grows high in the mountains with scant level land, requiring almost everything to be done by hand. Yet these mountain slopes have the ideal mix of volcanic soil, climate, and rainfall that coffee trees prefer. The strategy is to concentrate on quality rather than quantity, which has worked well, judging by the number of brands boasting 100 percent Colombian coffee.

Twenty minutes later, we arrived at the countryside home where the young farmer lives with his dog Chep. Nicolas built his modest but comfortable house almost entirely from local bamboo. There is nothing modest about the gorgeous view from the front verandah, with coffee trees against a backdrop of the intense green valley and mountain tops beyond.

The 2,000 or so coffee trees that Nicolas planted cover the steeply sloping land in front of the house. The older, larger trees farther down the hillside were established first, while newer plants cover the upper section. Trees are never allowed to get too high. When they become too difficult to reach from the ground, Nicolas cuts them down to start growing again.

While the main harvest seasons come twice per year, coffee beans are always ripening. Nicolas picks every 20 days. Even if a tree has only a few ripe beans, they still have to be picked. Overripe ones that fall on the ground are almost immediately infected by worms and become unusable.

Nicolas tied wicker baskets around our waists and invited us to get a taste of hand-harvesting beans. Judging by the meager selection of red beans in our baskets, it’s doubtful we would make it as professional coffee pickers, especially since they get paid by the kilogram, not by the hour.

Nicolas took us through the entire operation, from shaded nursery areas where he starts new trees, to the shed where he puts beans through a hulling machine to remove the outer shell, and the drying area. He spreads the beans out to dry on large trays on sliders. If it starts to rain, which it does a lot here, he can quickly push the trays underneath a part of the house built on stilts.

The Freshest Cup of Coffee Ever

Most producers take their dried beans to a buyer or to a cooperative for sale on the world market. Nicolas sends part of his production to a commercial roaster in a nearby town, then packages the beans to sell directly to consumers.

“I want to show you what coffee even fresher than that tastes like,” said Nicolas as he headed back to the drying trays.

He scooped up some beans that had been drying for a couple of weeks and put them in a pan covered by a lid with a crank on top. With the pan over low heat on the stove, we took turns working the crank for the next 20 minutes to keep the beans moving so that they didn’t burn. The beans made slight popping sounds, releasing an enticing aroma that filled the kitchen. This achieved a medium roast which Nicolas considers the best style of coffee with a balanced taste that brings out more complex flavours.

He then took the roasted beans outside and poured them from one container to another while using a tiny electric fan to blow away the lighter chaff produced while roasting. Then it was back to the kitchen to grind the beans and brew the coffee.

Grabbing our cups, we settled into chairs on the front verandah with the million-dollar view. Nicolas’ cows lazily grazed in the lush grass while flashy birds looking as if they had been dipped in paint flitted among the nearby branches. It seemed fitting that our finest-tasting cup of Colombian coffee ever was not in some fancy coffee shop but on the peaceful farm where the coffee was grown while sharing a cup with the farmer who grew it. More than a drink, it was savouring the essence of Colombia.

SUBSCRIBE to Photojourneys below

Feel free to PIN this article on Coffee Culture in Ethiopia and Colombia

Absolutely beautiful very interesting story about your adventurous trips to coffee farms! :)

Lillian – Thanks for your comment. It’s great that you enjoyed our coffee article. Cheers!