We just got back from witnessing one of nature’s most breathtaking spectacles. High in the Sierra Madre Mountains west of Mexico City is the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site where migrating Monarchs from east of the Rockies throughout North America overwinter in a mountaintop forest of oyamel fir trees. Arriving around late November and staying until March, they number in the millions.

We just got back from witnessing one of nature’s most breathtaking spectacles. High in the Sierra Madre Mountains west of Mexico City is the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, a UNESCO World Heritage Site where migrating Monarchs from east of the Rockies throughout North America overwinter in a mountaintop forest of oyamel fir trees. Arriving around late November and staying until March, they number in the millions.

Four main areas of the reserve are open to visitors. The largest and easiest to visit is El Rosario, up the mountain from the small valley town of Angangueo, which is reached by a 3-4 hour bus ride from Mexico City. At the reserve entrance, it’s still a bit of a walk uphill to get to where the Monarchs hang out. The altitude here is over 3,000 metres, so we had to take it easy in the thin air.

The first time that we saw a clump of trees thick with butterflies, it wasn’t immediately apparent what we were looking at. It was as if the branches were twice their normal thickness, but a closer look revealed layer upon layer of butterflies clinging to the branches. In places the masses were so thick that they completely obscured the green needles of the tree. While Monarchs have bright orange wings, they appear a more muted brownish-orange with their wings folded when resting.

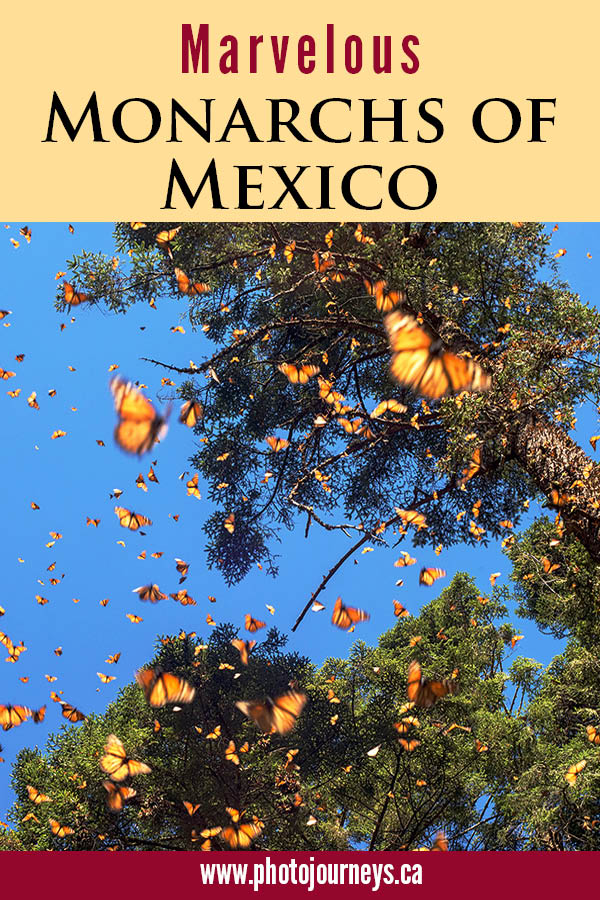

Early mornings can be quite cool, sometimes just a few degrees above freezing. If the weather stays cool, or even if it gets cloudy, the butterflies will stay on the trees. But as the sun gets higher and warmer, they take to the air in the thousands. Bold splashes of orange speckle the blue sky as countless Monarchs fill the air and land on branches, logs, the ground, and even on our heads and shoulders. The sound is unlike anything we have heard before: a gentle, whispering-like whir like a million pieces of confetti swirling in the air. Awestruck visitors speak in hushed tones, as they move slowly and carefully so as not to disturb or step on the countless butterflies.

Butterfly Migration

No other butterfly in the world migrates this far and in such large numbers. Their travels are more like bird migrations, but with a twist. Those arriving next year might be the grandkids or great-grandkids of this year’s migrants. How they find their way is still a mystery. It wasn’t until the late 1970s that researchers finally solved the riddle of where the Monarchs spend the winter. Of course, the locals knew they were there. But if you’ve always lived with butterflies, why would you think that it was anything unusual?

After a couple of hours, we leave with a feeling of exhilaration, tempered with the realization that this marvel of nature is threatened. Key parts of the forest are set aside as wildlife reserves, but there is constant pressure from logging interests. Altering habitats in Canada and the United States, especially the loss of milkweed favoured by Monarch caterpillars, is a serious concern. On a positive note, Monarchs help the local economy, long dependent on mining and subsistence farming. Locals run tourist services – everything from guiding in the reserve to providing transport, serving meals at food stalls, and renting horses to make the climb up the hillside – and have become major voices for conservation.

The best news is that it is easy and remarkably inexpensive to see this wonder of nature. Organized tours from Mexico City, Morelia, and other places abound, but visiting on your own is fairly straightforward (although it helps if you know a bit of Spanish). For the next posting we’ll outline details on the logistics of our visits to El Rosario and to another Monarch reserve – Piedra Herrada.

Feel free to PIN this article