All photos © Robin and Arlene Karpan

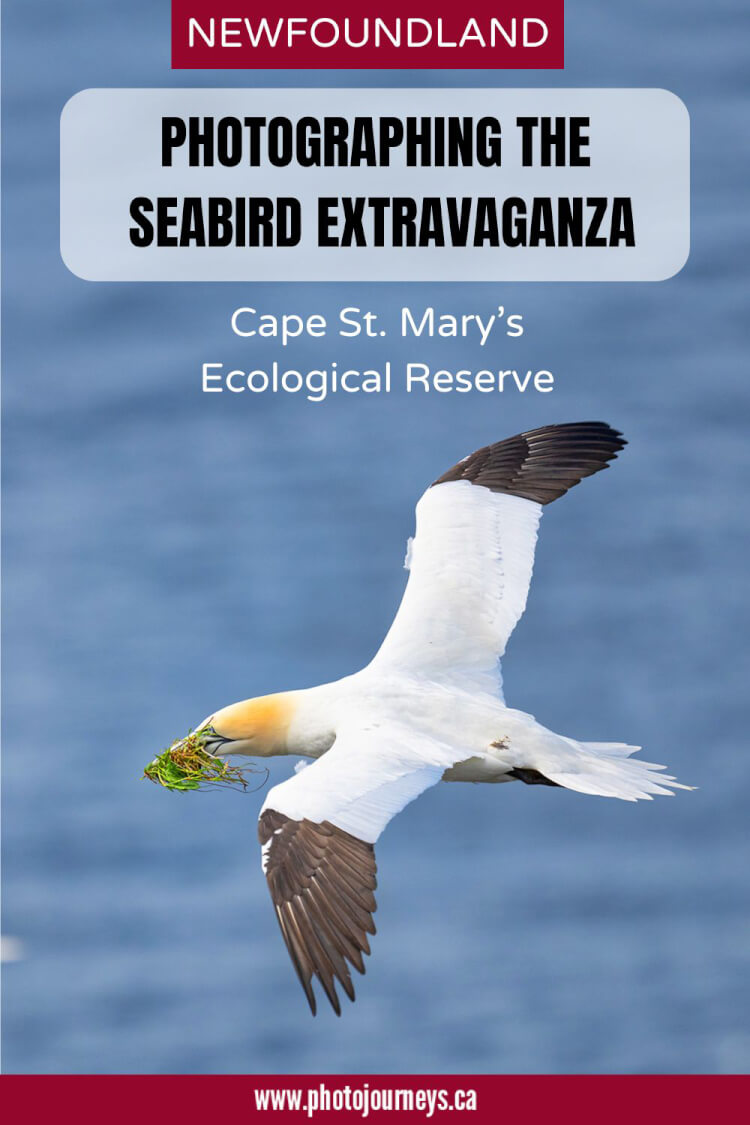

When it comes to watching and photographing nesting colonies of seabirds at close range, nothing can compare to the rare experience at Cape St. Mary’s Ecological Reserve. Located on the southwest corner of Newfoundland’s Avalon Peninsula, it’s the most accessible seabird rookery in North America, home to thousands of birds including gulls, razorbills, black-legged kittiwakes, common and thick-billed murres, cormorants, scoters, various ducks and more. Stealing the show, however, are the thousands of northern gannets during the summer nesting season. It’s one of few places in the world where we don’t have to take a boat to see northern gannets.

The Ecological Reserve is about a 2.5-hour drive from the capital city, St. John’s. We can drive right up to the Interpretive Centre and from there it’s an easy walk of just over a kilometre to a strategically-situated viewpoint over the main rookery. Most of the gannets nest on top of a 100-metre high sea stack called Bird Rock, separated from the cliff-top viewing area by only a few metres. The vantage point is ideal. They’re so close, but remarkably, the birds pretty much ignore us and they carry on with their regular nesting and feeding activities.

Northern gannets spend most of their lives at sea. They are drawn here by the abundance of food found nearby where the cold Labrador Current meets the Gulf Stream. Their excellent vision helps with their dramatic way of fishing where they dive-bomb into the water, often plunging deep to snag a fish. They breed in Eastern Canada and northern Europe. Of the six colonies in Canada, three are in Newfoundland and three are in Quebec, with the largest being Bonaventure Island just offshore from Perce in Quebec. Cape St. Mary’s is the world’s most southerly colony.

Once the prime nesting sites are taken on Bird Rock, the gannets spread onto other nearby cliff faces. The cliff edge viewing area is a wonderful place to pull up a comfy rock and watch and photograph the action. There’s always something going on as the birds fill the air as well as the nesting grounds. We watched several come back to the nest with mouthfuls of seaweed to add to the nest. Most fascinating was watching them land. Because the nesting area is so crowded, they often try to hover in the air to get lined up, and then drop into place. This is an ideal time to photograph since the action slows down for a few seconds.

Another behaviour to watch for is “necking” when a gannet pair greets each other by raising their heads and necks and rattling their bills together. Living in such close quarters often results in squabbles breaking out between neighbours.

While gannets are the star attraction, don’t overlook the goings-on of other species. The kittiwakes often make quite a fuss, and the razorbills frequently display by raising their heads straight up and calling out while showing off the bright yellow inside of their mouths.

The Photographic Experience

Since we are so close to the action, it’s possible to get away with shorter focal lengths than are usually necessary for bird photography. However, we would still recommend taking the longest telephoto lens you have. We did most of our photography with a 180-600mm zoom. This was ideal because it allowed for frame-filling shots at 600mm but it was easy and quick to zoom to a shorter focal length to include more of the environment or when a bird came very close. For in-flight shots at close quarters, it is often easier to find and track the bird with a shorter focal length. We also used a 24-120mm lens for some overview shots and scenics.

Settings will of course depend on light conditions. We were fortunate to have ideal light, even though it was close to midday which is normally not the best time for photography. Slightly overcast conditions cut down on the harsh midday light but it was still bright enough to allow for fast shutter speeds without setting the ISO excessively high.

Because you drive to the site and can stay as long as you like, this is the ideal time and place to experiment with different settings. For a portrait of a bird sitting fairly still, you don’t need the fast shutter speeds of birds in flight.

A technique that we often use for flying birds is to manually set the aperture wide open, set the shutter to a fairly fast speed (minimum 1/1000 sec. and as much as 1/4000 sec.) and then set the ISO to auto. This ensures that we always have a fast speed to try to stop the action because the ISO setting changes automatically according to the light. See our separate posting on using auto ISO for wildlife photography.

We brought a tripod to the site but didn’t use it much since handholding was more convenient for the action photos we wanted. However, a tripod would be useful in lower light.

Take advantage of the breathtaking scenery

Like most first-time visitors we were anxious to walk straight to the main lookout point. But on the way back we took our time and followed some side trails to other lookout points. Besides amazing birds, the scenery is stunning with soaring cliffs and a rugged shoreline. This area is part of a unique landscape known as the Eastern Hyper-Oceanic Barrens, a rare piece of tundra covering the southern part of the Avalon Peninsula. The open countryside has Arctic-like wildflowers and wildlife such as ptarmigan and caribou.

How to visit Cape St. Mary’s

We visited Cape St. Mary’s as part of a larger naturalist’s tour of the Avalon Peninsula led by Jared Clarke of Bird the Rock who is one of the most knowledgeable bird experts around. If you have a car, you can also simply drive to Cape St. Mary’s on your own. Best of all, there is no admission charge to visit the site or the interpretive centre which is open from May to October. Dress appropriately since it can get cool standing on the cliff edge, and fog, wind or rain could happen anytime.

Even if you go on your own, you won’t be without guidance. Be sure to first stop at the Interpretive Centre to see the exhibits. A park interpreter is often on hand at the viewing area to answer questions, help with bird identification, and provide further details.

We lucked out with glorious weather on the day of our visit in mid-June but it isn’t always like this. “I’ve been working here for 23 years,” said interpreter Chris Mooney, “and this is the only time I can ever remember having two sunny days in a row.” Normally the cape lies enshrouded in fog for some 200 days a year, resulting in cool and damp conditions. Visitors are still able to see the birds up close, but viewing longer distances is more limited.

Mooney obviously thoroughly enjoys his job. “I never get sick of it. I could spend all day watching the birds. Nobody’s got a better office than me.”

Resources and further reading

- Cape St. Mary’s Ecological Reserve

- Newfoundland and Labrador Tourism has a wealth of information on other birding sites and places to explore in the province.

- Destination St. John’s for information about the capital city. You can do a day-trip to Cape St. Mary’s from St. John’s.

- Bird the Rock offers guided tours to Cape St. Mary’s and other birding hotspots in Newfoundland, run by birding expert Jared Clark.

- Also check out our posting on the famous Jellybean Row Houses in St. John’s

SUBSCRIBE to Photojourneys below

Feel free to save this PIN on Cape St. Mary’s Ecological Reserve in Newfoundland for later

Excellent information in this photojourney. We didn’t get to the Avalon Peninsula so we will just have to go back. We did see the Northern Gannet Colony in Perce, Quebec the beginning of June. I’ve never seen so many at one time. We were on a boat though so it was very hard to photograph. Thanks again for sharing these wonderful articles.

Good to hear that you enjoyed the article Amy. Yes, the Perce colony is so impressive as well. If you’re back that way try to arrange to go onto the island right to the colony to see and photograph the gannets. It’s an unforgettable experience. See our article https://photojourneys.ca/2022/11/gannet-wildlife-adventure-bonaventure-island-quebec/

Very helpful and relevant information for our visit tomorrow.