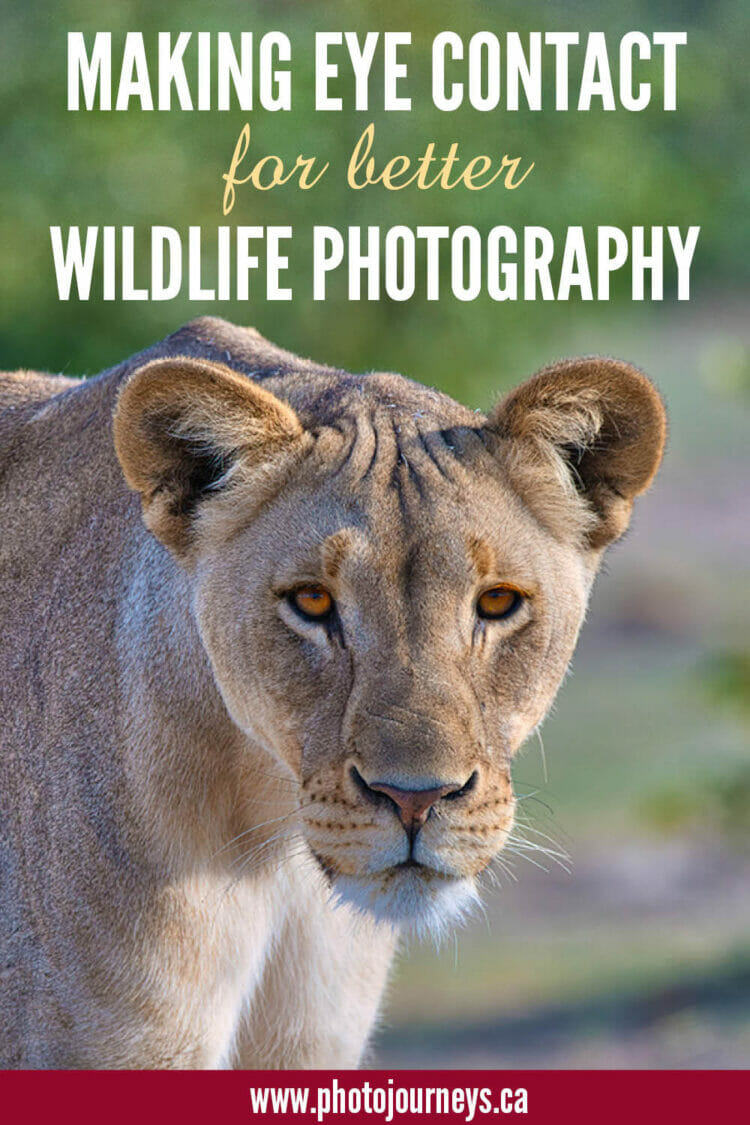

It’s all in the eyes. It’s human nature for us to to be drawn to the eyes first, whether we’re looking at people or animals. In wildlife photography, the goal is usually to focus on the eyes. A wildlife image that is partially out of focus might still be effective as long as the eyes, or even one eye, is in focus.

Get to Eye Level

Being at the same eye level as your subject makes more of a connection and a more intimate photo. You show their perspective on the world. That’s usually less of a problem with larger animals, but it can be more challenging with small critters, such as with birds swimming, on the ground, or perching high in tree branches.

There are also some technical reasons for getting to eye level. The photo is usually sharper because the camera sensor is parallel to the animal’s face rather than being at an angle. The background tends to less distracting as well. When we look down on an animal, we often get more of the background in the image. But at eye level, it’s easier to focus only on the subject and throw the background out of focus, making the animal stand out more.

When trying to get to eye level, often only a slight change can make a big difference, such as crouching down to take the photo or lowering your tripod. To really get serious, try lying on the ground. When you can’t get to a lower level, staying farther back and using a longer lens may help to minimize the difference in height. The farther away you are from your subject, the less extreme the angle will be between your height and their height.

A telephoto lens is especially useful when you’re photographing from your vehicle and don’t have much choice as to how high you are off the ground. Staying in your car is often the most effective way of getting reasonably close to some wildlife without spooking them, not to mention staying safe when photographing bigger critters such as bison, bears, or lions. See our post Use Your Car as a Photography Blind.

Let’s say that you find a wetland beside the road with several ducks and grebes. If you photograph a bird close to you, it’s necessary to point the camera down somewhat. But if you focus on a bird that is a bit farther away, you don’t have to point the camera down as much. So even though you aren’t physically lower, the angle between your height and the bird’s height is less pronounced, giving the impression of being closer to its level.

The same goes for birds in trees. Looking up at a bird high in the tree is a less pleasing angle. Depending on light conditions, there could be the added challenge of balancing the exposure for both the bird and a bright sky. Ideally, take the shot when the bird is on a branch closer to your eye level, or go back farther to reduce the angle.

The Eyes as Part of Photo Composition

Where the eyes are directed also affects the composition of a photo. When we see a portrait of an animal, we’re inclined to first look at its eyes, then follow its gaze. If the animal is looking left, we tend to look in that direction as well. If the animal is looking towards the centre of the photo, our eyes tend to do that as well. So whenever possible, it helps if the subject is looking into the scene rather than to the outside, keeping our eyes in the scene.

Look Them in the Eye

The animal’s eyes don’t have to be looking back towards you for the photo to be effective, but it does add another dimension to the image. We can’t know what an animal is thinking, but when it sees you and doesn’t flee or make threatening moves, it indicates some level of acceptance, or at least tolerance, of your presence.

The other strategy is to simply be patient, observing wildlife at a distance that they don’t find threatening, and wait. Wildlife that accepts your presence may simply go about their business, though it’s not unusual to glance your way every so often.

That’s exactly what happened with this badger. It had spotted a gopher, its favourite food, but wasn’t able to catch it before it ran down a burrow. The badger was determined to find the gopher and started digging furiously. It knew I was watching, but I was sitting in my truck far enough away that it tolerated me. But every so often it stopped digging for only a second or so, just long enough to look up to see that I was still far enough away. It provided a great opportunity to not only get actions shots of the digging but also a badger portrait with eye contact.

Other articles on photography that you might enjoy on Photojourneys

- How shooting in RAW gives you better control over your photo content

- Using a telephoto lens for landscape photography

- Discover the benefits of using Auto ISO for wildlife photography

- Some tips to consider to improve your bird photography

- Experiment with photographing abstract patterns in nature

SUBSCRIBE to Photojourneys below

Feel free to PIN this article on Making Eye Contact in Wildlife Photography

that is so cool

We’re glad that you think so. Thanks for commenting.